When Fujifilm re-entered the ILC market with the X-Pro1 in 2012, I have to admit that while I was impressed with the hybrid optical/EVF viewfinder, the rest of the camera felt a performance laggard to me. I also had serious qualms about the X-Trans sensor design, as well.

Fujifilm then wandered around with some X-E, EVF-only rangefinder designs. It wasn’t until 2014 and the very DSLR-like X-T1 that it felt to me that Fujifilm was starting to get back to where they were early in the DSLR era with their S-Pro cameras. Indeed, the X-T1 seemed to go further, drawing more upon classic ILC designs than before.

From left to right: X-T30, X-T3, X-H1, X-T100.

It’s hard to believe it’s only been five years, but we’ve now had three X-T#'s, three X-T#0’s, an X-H1, and even an X-T#00 filling out this SLR-like line. That’s a lot of iteration and extension in the SLR-like space in a very short period of time. I’ve been a bit behind in reviewing models for a couple of camera companies, and decided that the Fujifilm APS-C mirrorless lineup was a very good place to start trying to correct that.

Thus you’ll see that I’ve now posted reviews of the X-H1, X-T3, and X-T30 in addition to my already posted review of the X-T100. I've also added some more Fujifilm lens reviews, as well (more on lenses at the end of this article).

With all this review catch up, I decided I should also write a short article that went beyond the reviews to give a better sense of where I think Fujifilm is overall with their APS-C camera lineup.

Leaving out the X-Pro2, which is due for an update and is likely only going to appeal to a very specific type of shooter, the core of the Fujifilm lineup from bottom to top goes like this:

- X-T100

- X-T30

- X-T3

- X-H1

The H1 is above the T3?

Yes, in my mind it is. It’s a very impressive camera that I believe is at the top of the Fujifilm heap. Curiously, the X-H1 didn’t sell well at it’s original price, and thus has recently found itself sale priced below the slightly newer X-T3.

One issue that Fujifilm faces with pricing is the APS-C sensor size they use in the XF line. With full frame bodies now starting at US$1300, the US$1600+ that Fujifilm wanted to charge for the top end of its line became an issue. The X-T3 came out at a price US$100 below that of the X-T2 it replaced, despite having a new sensor and more performance, so it’s clear that Fujifilm itself was aware of their dilemma.

I’ve written about the “camera squeeze” before. At the top end we have truly remarkable full frame and now medium format cameras. The bottom end of full frame keeps reaching downward in price, putting a squeeze on the top end of smaller sensor cameras. We have Sony promoting one-generation-old A7m2’s at the US$1000 (or less) sale price, while Canon with the recent RP at US$1300 list price has already also offered some modest discounts. We’re going to see more and more full frame activity just above the US$1000 point.

Meanwhile, at the bottom, smartphones slowly get more and more competent and keep gobbling up entire camera categories. First it was very small sensor, inexpensive compacts that caved in, but that nibbling has now reached to just below the 1” sensor cameras, and I don’t think it will stop there.

The net net is that many people feel that they get a very competent camera when they spend US$1000 for a new smartphone. If they want an excellent-performing full frame camera, that’s now at or under US$2000, depending upon promotions (e.g. Nikon Z6, Sony A7m3). But they also have good options that are less expensive than that. Current full frame prices for a solid, new camera range from US$1300 to US$2000.

Meanwhile, Fujifilm is competing against one of the most venerable crop sensor cameras ever made, the D500. That Nikon DSLR is currently running at US$1500 as I write this, but has been as low as US$1300 “with extras” at times.

This is a long-winded way of saying that Fujifilm is trying to squeeze a lot of SLR-like product into a narrowing price window. Given that the X-H1 apparently didn’t sell up to expectations, you have to wonder if there will be an X-H2. Even though Fujifilm is a deep-pocketed company where cameras are only a minor blip on their financials and thus can tolerate a bit of financial underperformance, I’m pretty sure that Fujifilm is entering into a period where they need to whittle down their lineup a bit.

At present, we’ve got seven “current” XF cameras (X-A5, X-E3, X-T100, X-T30, X-T3, X-H1, and X-Pro2), slotted from about US$500 to US$1700 for body only. That’s more than enough. I believe having that many products in the smartphone-to-full-frame gap also introduces marketing issues, as well, as I’d defy most salespeople to correctly identify the weaknesses and strengths of each one and why a prospective customer should buy a specific one.

Moreover, Fujifilm is overstocked at the higher price points, and the models aren’t quite distributed right in the middle points. While the high-volume Canon and Nikon APS-C DSLRs tried to carve price points every US$100 or tighter at one time—using previous generation bodies to fill in the gaps—I don’t think that’s the right approach in a contracting market. The camera companies do that to clear inventory and sensor commitments, and they think that this is “working.” Realistically, though, we’re in a market with deep overstocking of product, poor clarity between products, and a lot of confusion facing buyers that haven’t done much research when they walk in the door.

I personally see something like US$500, US$750, US$1000, US$1250 as the current (and only) logical APS-C price points given the squeeze happening at the two ends. And probably those two inner points shouldn’t be linear, but curved slightly more towards the lower boundary (e.g. US$500, US$700, US$900, US$1250). Moreover, I don’t know how long you can get away with five or more models in that squeezed realm.

But all that would be arguing in the weeds, where I want to show the forest here. The forest says that APS-C basically sits from US$500 to US$1300 now. Anything else and the product would have to be distinguished far from current cameras in some way.

So where’s that leave us with Fujifilm’s current lineup?

Well, that X-H1 is at US$1300, and I think that’s the right price for such an excellent APS-C camera. As much as Fujifilm would like me to write that it’s the equivalent of a D500, I don’t believe it is. It falls short in a couple of ways, though it also does a bit better in a couple of others, mostly associated with build quality and IS. Meanwhile, the D500 tends to get its benefits from a better AF system and a wicked solid frame rate and buffer, coupled with a wide range of desirable lenses in the telephoto realm, which frankly, is where most people buying a high performance APS-C camera are going to want to tread.

(To Fujifilm: one reason the X-H1 underperformed is the lens lineup. At the high APS-C level, Fujifilm just doesn't have the extensive telephoto lens lineup that's necessary to fully attract wildlife and sports shooters.)

At the other end of Fujifilm’s lineup, the US$450 X-T100 is a screaming bargain these days. While it has plenty of areas where it isn’t state-of-the-art or a high performer, what US$450 camera is full featured and beefy? The 24mp Sony sensor inside is well-proven to be excellent in capability, and Fujifilm exposes enough features and control in the base model that someone knowing what they’re doing can extract remarkably good image data out of the X-T100 (Hint: if you want a camera to convert to IR and you’re a Fujifilm user, this is the one I’d do that with. Okay, maybe the X-A5, as well, if you can live without the EVF).

The camera that surprised me this round of testing was the next model up, though, the US$900 X-T30.

To describe why, I need to devolve into another discussion revolving around APS-C: size. Final camera/lens size and weight, to be particular.

With highly competent full frame cameras hovering just above, a good APS-C product has to have some clear and significant selling benefit. The Nikon D500 I already mentioned gets its big selling benefit from being a smaller, far less expensive D5. It’s optimized in much the same way as a D5: slightly smaller sensor pixel count to preserve high ISO capability, really fast frame rate with excellent autofocus performance, plus a deep buffer backed by a fast card mechanism.

There are other ways to stand out. And I think key among them is the size/weight thing. Hanging a five-pound weight around your neck and carrying it all day while traveling is no longer compelling ;~). I’m not sure it ever was, but we put up with it because of the image potential coupled with the fact that everything else was also that big and heavy.

APS-C sensors have enough image potential in them for most people for most purposes, but their smaller size can (and should) also be reflected in smaller body and smaller lenses.

And that’s where the X-T30 comes in. It’s a very small, light body with a lot of capability. Couple it with the right Fujifilm lenses—the surprisingly excellent 15-45mm f/3.5-5.6 comes to mind as a reasonable general purpose lens—and it will fit in a jacket pocket or a very small accessory bag, making it a compelling travel camera. Quality would easily best your smartphone, you have the flexibility of interchangeable lenses, you’re not encumbered by much size or weight if you choose lenses wisely, and you also haven’t spent as much money as a low end full frame user.

This is exactly where Canon is trying to live with the EOS M, and I believe that it’s where the best part of Fujifilm’s efforts tend to lie, too. I can definitely recommend the X-T30 to a lot of folk, particularly with the smaller prime lenses and zooms in the Fujifilm lineup.

Which brings us to the X-T3 and X-H1: both are essentially DSLR-sized cameras. Their build quality adds weight and bulk. The thing that people tend to be interested in doing with these cameras is compete with the full frame shooters. They expect top-of-the-line focus, frame rate, buffer, and viewfinder performance, and much more.

The problem is that the window at the top is even narrower than the overall APS-C window. By the time you get to the US$2000 point, I believe that you have full frame cameras that can do everything most people would want. Moreover, if you start sticking on faster lenses on the APS-C to match the full frame image performance, what I keep finding is that you’ve lost much, if not all, of the size and weight advantages with APS-C. You may have even lost a lot of the price advantage, too.

Thus, you have the X-T3/X-H1 starting to compete with the Sony A7m3 and Nikon Z6, and this is only going to get worse as the full frame makers start doing more dramatic discounting to keep volume moving.

All of which is to say, as I began testing the X-T3 and X-H1 they had very high bars they needed to clear. To their credit, they mostly do, but they’re very near the top end of what APS-C is going to manage in the future, I think. That pricing pressure that forced the X-T3 to list for less than the X-T2 originally did is only going to increase. Don't be surprised if an X-T4 has to list for less than the X-T3 did when it first came out. It's either that or it needs to get up to the D5/A9 level of performance at a lower price.

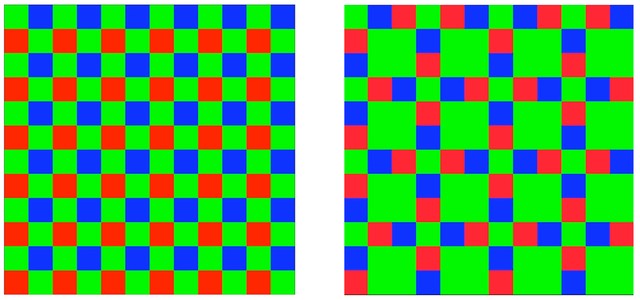

Bayer pattern on left, X-Trans pattern on right. Pay close attention to the red photosites. Do you see how they're evenly spaced and lined up in Bayer? Now look at the alignments in the X-Trans pattern: you should see that diagonals offset a bit, while there's not even spacing on the vertical/horizontal axis. On the other hand, there's more green (luminance) information in X-Trans.

Meanwhile, it's time to address X-Trans versus Bayer again. Dr. Bayer himself explored many other filter patterns beyond the one that his name is associated with, including some X-Trans-like ones. Bayer came to the (arguably correct) conclusion that the RG/GB layout was the most efficient. You can make more complex layouts that gain some specific benefit if you have enough pixels, but each of those have their own demosaic problems to solve and can introduce additional liabilities, as well. Basically, non-Bayer patterns may turn out better at one thing, but then turn out worse on another.

Fujifilm sacrificed color information for luminosity information in opting for X-Trans. They're not alone in that. Many of the camera companies have been quietly degrading Bayer filtration strength in ways that sacrifice some color information for more light reaching the sensor.

Fujifilm made a big claim early on about elimination of color moire by using X-Trans. They then backed off that to just claim a "reduction" when many of us pointed out that their statement wasn't true. X-Trans does reduce production of color fringing in most instances, but it came with another problem: color pollution on fine detail. I demonstrated that in my X-Pro1 review, but here's the thing: both Bayer color fringing and the X-Trans color smear tend to happen at such a low level of detail that most people never see it. As sensor pixel counts go up—X-Trans has gone from 16mp to 26mp—that "low level" tends to get buried deeper (unless you use extra pixels to print larger). Moreover, with tuning of the demosaic, you can mitigate either problem further.

Indeed, that's exactly what's happened over time: the X-Trans demosaic routines in raw converters have gotten better even as megapixel counts have gone up. This reduces and masks the effects of color smearing. Curiously, the Adobe converters are still among the worst in rendering fine detail in X-Trans images, but they still do a credible job now, and more pixels means you're less likely to see those effects pop way up into visibility.

So X-Trans has become a bit of a non-issue over time. Is it a benefit, though? I'm not convinced it is (other than for those making black and white conversions from the underlying data, due to having more luminance data to work with). You get a few percent more luminosity data, but that's simply not enough to narrow the dynamic range gap to full frame sensors significantly.

In essence, we're down in the weeds when we start trying to evaluate Bayer versus X-Trans at APS-C sizes. Indeed, the Bayer sensor in the Fujifilm X-T100 tends to produce pretty much the same level of results as the older 24mp X-Trans sensors in the X-T2 generation cameras, but without any low-level color smearing (another reason why I recommend those Bayer Fujifilm's for IR conversion; the Bayer pattern doesn't complicate the resulting data).

One problem that Fujifilm users haven't figured out yet, though, is this: doing pixel shifting with X-Trans will be a bit of a challenge. Because of the big GGGG box in the center of the larger X-Trans repeating layout, you'd have to do a more sophisticated shifting to get RGB data out of each site. (I suppose that there might be a clever shift possibility that's useful, but it might require more demosaic trickery.) That has impacts on file size and motion artifacts, which is probably why Fujifilm hasn't added that feature to their cameras.

Still, I'd tend to say that today X-Trans isn't as much a liability as I thought it once was. But nor is it a big gain as Fujifilm marketing suggests. They've simply taken a slightly more complicated filtration route that produces slightly different pros and cons in the underlying sensor data to produce what turns out these days to be nearly the same result (at least assuming you use an optimal converter).

Finally, one thing I've noticed quite a bit as the full frame mirrorless market matured and Canon and Nikon joined in is this: I get more and more email from "former" Fujifilm users. Those folk mostly switched from Nikon DX when Nikon basically ignored the DX lens situation (and serious mirrorless cameras, too). Fujifilm's more traditional camera designs—dials, mainly—and complete APS-C lens lineup, particularly in primes, appealed to those Nikon DX users that felt ignored.

Unfortunately, many didn't stay Fujifilm users. Quite a switched again for Sony or Nikon full frame mirrorless once it matured (or appeared on the Nikon side). This indicates to me that Fujifilm caught some trend that was present for awhile, but then didn't fully satisfy it. I'm not entirely sure what the missing element was, but in exclusively using so much Fujifilm gear recently I have to say I did feel like I was going a little bit backward.

Tracking focus performance in all the Fujifilm models was slightly behind what I'm used to now in mirrorless, and other little things tended to make me more aware of the camera than I like to be while shooting (again, small buttons that are hard to find by feel should be outlawed). Adjusting two dials to change exposure modes is slower than the modern alternative. None of these things are deal stoppers, at all, but I did notice them (and others).

That said, Fujifilm at the moment has a very nice line of XF camera choices using APS-C sensors, coupled with a mostly full line of APS-C lenses that is only missing some telephoto choices now. A nicer and more complete lens line than anyone else in APS-C. Perhaps too extended on the camera side, though, and needing some careful product line management choices when iterating the coming 4-generation cameras, but still, what Fujifilm is doing with XF is very nice overall.

Thus, if you're a serious general purpose APS-C shooter, I'd say that today Fujifilm is your best choice. That's because:

- In the DSLR world, Canon (EF-S) and Nikon (DX) basically went "all consumer," and mostly serve up low-cost convenience cameras and lenses. Where Canon and Nikon do have higher end products (e.g. 7Dm2 and D500), they haven't supported them with a full lens set: they seem to target those only to birders and sports action shooters using full frame lenses.

- In the Canon mirrorless APS-C world (EOS M), the emphasis seems to be on very compact cameras with modest build quality, and again only with consumer convenience lens choices. Just to be clear: I'd choose an Fujifilm X-T30 over the Canon M5, mostly because of lens choice (but also partly because of sensor and lens performance).

- In the Sony mirrorless APS-C world (E mount), you have one basic camera that has been updated into four (A6000, A6300, A6400, A6500), and you may not like that camera design at all. Lens choice originally looked like it would fill out, but Sony abandoned that work to produce more full frame lenses, so your overall lens choice is more limited with Sony than Fujifilm; serious Sony E-mount lens choices are seriously more limited than Fujifilm XF. Indeed, lenses like the Sony 16mm f/2.8 may look like equivalents to Fujifilm lenses, but when you measure their performance, the Fujifilm lenses win every time.

So what it really boils down to is this: are you a serious APS-C shooter?

I'm not sure what would define you as such a photographer any more, unfortunately. As I noted above, full frame camera pricing is coming down (as did the size/weight), so Fujifilm finds themselves in a squeeze. As I noted, the X-T3 and X-H1—the most desirable of the Fujifilm bodies—start to get close to as big and heavy as the lightest full frame offerings, particularly when you load the Fujifilms up with faster lenses. It would be difficult for me personally to justify an X-T3 over a Z6 or A7m3 because of that.

What I keep coming back to are the X-T100 and X-T30, for different reasons. The X-T100 is an out-and-out bargain when it comes to price/performance. A great sensor on a truly consumer body, but at a very affordable price. I've had an X-T100 kicking around in my bag for awhile now, particularly once I found out how good the 15-45mm kit lens is.

But the X-T30 impressed me, too. True, the build quality isn't as robust as its bigger brothers. But it's a smaller camera and thus also highly travel-worthy. If you pick the right lens(es), it also doesn't become the huge neck-weight or require the bag volume that DSLRs got their reputation from.

Fujifilm's built a solid lineup of APS-C cameras and lenses. I can certainly recommend them, particularly if you fall into one of the camps that value particular aspects of the XF system. The large and growing prime set will be very tempting for many, I'm sure. I've yet to find a dud among those (which is more than I can say for Sony E-mount).

Moreover, each generation of Fujifilm's cameras has made clear strides forward in features, handling, and performance, to where today they essentially form APS-C state-of-the-art (the Nikon D500 notwithstanding).

So, nice job Fujifilm. You've carved out a small piece of the market and mastered it. I hope you can hold onto it.

One final thought: you may note that the three big, Japanese, third-party lens makers (Sigma, Tamron, and Tokina) aren't doing much in the XF mount. Zeiss initially did, but that was because of direct interest and help from Fujifilm in getting more lenses out of the gate. Since those initial Touits, we haven't seen anything else from Zeiss.

You do see a number of the smaller, manual-focus-only lens makers changing out the mount area of existing designs to support Fujifilm, as that's a rather easy, low-cost thing to do and broadens the market for their offerings.

But here's the rub: as much as you Fujifilm fans enjoy your cameras, there aren't enough of you yet. Couple that with Fujifilm themselves filling out the lens lineup, and there aren't enough dollars on the table for serious investment in new lens designs for XF from others.

To me, you have to like what Fujifilm is doing, because Fujifilm is likely supplying both the camera and lenses you'll purchase. That's one reason why I tried to get some additional Fujifilm lenses reviewed in this batch of camera reviews: the two really do go together. And the sum of those two parts is overall excellent, something I can't say about EOS M or Sony E.