Get out your reclining chair and some popcorn. This is going to be a long and somewhat controversial review. Of course, I’m reviewing two cameras, so long might be expected…

Source of cameras: A7 was purchased from my dealer; A7r was borrowed from B&H (disclosure: B&H is this site’s exclusive advertiser).

Oops. The lens hood on my 35mm sample keeps moving from the click-in lock position. A7r with 35mm f/2.8 on left, A7 with 28-70mm kit lens on right.

What Are They?

The Sony A7 and A7r are the first full frame mirrorless cameras from a Japanese manufacturer, and both generated a very large buzz on the Internet from their introduction through initial sales. After the cameras got into user hands, the buzz seemed to die down a bit.

By full frame I mean a frame size equal to those of 35mm film cameras and DSLRs such as the Canon and Nikon professional cameras (FX in Nikon parlance). The full frame 24x36mm sensor size is significantly bigger than the APS crop (16 x 24mm) NEX models previously in their mirrorless lineup. The exact two sensors used in the A7 models are ones that have gotten quite a lot of acclaim in other cameras, including the 36mp Nikon D800 and D800E. Yet both A7 models are less expensive than DSLRs that use the same sensors. Sony is playing the smaller, lighter, less expensive game here, hoping that the things that are different in the A7 mirrorless models from those higher priced DSLRs aren’t valued highly enough to make a tangible difference to potential customers. We’ll get to whether that’s entirely true or not in the performance and final word sections of this review later, but no matter what you think about the cameras' abilities you have to be impressed with how aggressively Sony has designed and priced these cameras.

It’s probably best to start with the differences between the A7 and A7r, because they are few:

- A7 — US$1700 body, 24mp (6000x4000 pixel) sensor with phase detect autofocus capability, AA filter over the sensor, the sensor has offset microlenses, plus a faster 2.5 fps frame rate for continuous shooting (5 fps without focus/exposure changes).

- A7r — US$2300 body, 36mp (7360x4912) sensor with no AA filter and no offset to gapless microlenses, and a slower 1.5 fps continuous frame rate (4 fps without focus/exposure changes). The A7r does not have an electronic first curtain shutter that only syncs to flash at 1/160, and it has a bit more high end build in a few of the body parts, particularly the front plate. The A7r has only contrast autofocus.

Many folk get excited about the 36mp number of the A7r (in particular, because it’s like the D800E, without AA over the sensor). Yes, that’s the highest megapixel count we’ve got as I write this for consumer cameras, and that Sony sensor performs at the very highest levels I’ve measured. Since there’s also a 24mp camera (A7) I should also point out that 36mp versus 24mp isn’t the 50% improvement you think it is. Technically, the linear resolution difference is about 23%. As I’ve written elsewhere, it takes 15-20% resolution change to be clearly visible to most people, so we’re just barely above that bar. People who expect that the 36mp A7r is going to be stunningly better than the 24mp A7 may be a bit disappointed. Indeed, I’d tend to say that the removal of the AA filter on the A7r is likely to produce a more meaningful visual difference for most people than the extra pixels.

While the A7 and A7r have an E-mount on the front, all those E-mount lenses designed for the NEX cameras were designed for crop sensors (APS) and most don’t come close to covering the full frame. The default is for the A7/A7r cameras is to automatically recognize APS lenses when put on the camera (which might make you think that you’re recording on the full sensor since you see what looks like a full frame in the EVF), though you can cancel that via a menu setting.

The mount in the A7 and A7r is technically called the FE mount. If you buy an FE lens, it will cover the full frame sensor of the camera. As I write this, there are only four FE lenses available (35mm, 55mm, 28-70mm, and 24-70mm), with more having been pre-announced. I'll write about lenses a bit more later in the review. If you want to see Sony’s plans for FE lenses, see this page.

Both cameras feature a small DSLR-like design with a prominent EVF hump up top. The EVF is the 2.4m dot, fast refresh one that Sony has used before (as has Olympus in the OM-D E-M1) and has a respectable 0.71x magnification and a fairly wide diopter adjustment range, too (+4 to -3m). Out back is a 3” 921k dot tilting LCD that can fold 90° up or 45° down. Eye detection at the EVF can turn off the LCD when you look through it and turn it back on when you remove your eye from the viewfinder (default behavior).

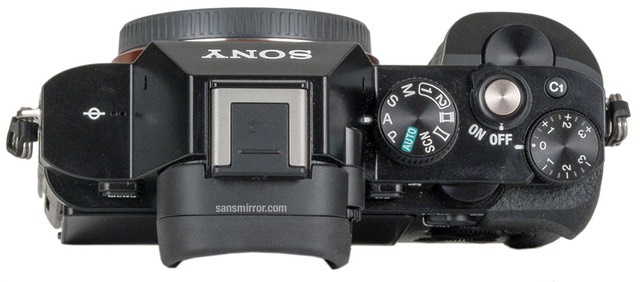

Up top of both cameras is a simple Mode dial, an On/Off switch around the shutter release, an exposure compensation dial and a programmable button (C1), all on the right side. The Mode dial has two user settings positions, plus access to Auto, Scene, Panorama, and Video shooting as well as the usual PASM choices. A hot shoe sits atop the EVF hump. Overall, the top of the camera seems very DSLR-like.

The back of the A7 models is once again trending away from the old NEX-style three-button interface. Sony’s recent experience with the RX cameras now seems to be influencing their choice of controls and menu styles on the mirrorless cameras, which is probably a good thing, though a bit of concern to those coming to the A7 directly from a NEX model, as they’ll be learning new ways of controlling the camera.

In particular, the A7 models have front and rear command dials, much like high-level DSLRs do. Beyond that, we also have several more programmable buttons (Fn, C2, C3, and more), though we still have things assigned to the edges of the Direction Pad ala compact cameras.

The Menu button is oddly positioned to the left of the EVF. I write “oddly” mainly in comparison to other Sony designs. I suspect that there was a large emphasis on getting active shooting controls all under the right hand and things that are used less often, like the Menu button, out of the way. Speaking of out of the way, Sony has moved the Record video button to a very out-of-the-way place on the right top edge of the camera (barely visible in image, above). It’s also recessed. Bravo.

The bodies have both plastic and metal aspects to them, though the A7r has a bit more metal inside it; both weigh in at about a pound (465g). By comparison, the Nikon D800 models are almost two pounds. The impression is still one of density when you pick up either the A7 or A7r, as they are in a small package with a still substantive weight.

Both cameras take the NP-FW50 battery Sony has been using the NEX line, rated to 340 shots CIPA on the A7 and only 270 shots CIPA on the A7r. While the battery inserts into the bottom of the camera as you’d expect, both the A7 and A7r have a dedicated card door on the back right edge of the camera, another nice touch from most mirrorless camera designs, and very DSLR-like.

If you’re into video, both cameras have 1080P available in a useful range of frame rates: 24P, 25P, 50P, and 60P. 50i and 60i are also available. Unfortunately, we’re still in AVCHD territory here, with it’s inherent folder/file structure complexity and limited bandwidth compression (28Mbps).

A comment about lenses. With the move away from "NEX" to everything being Alpha, Sony is also offering up a lens cacophony that you need to understand. Here's how things work on the A7 and A7r:

| Lens Mount | Sub Identifier | Image Area Covers | Requires | What Happens on A7 and A7r Cameras |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-Mount | no modifier | APS crop sensor | nothing | At defaults, image cropped to the APS frame size; with this option turned off, the lens generally doesn't cover the full frame (clipped corners) |

| FE | full frame sensor | Full frame is covered | ||

| A-Mount | DT | APS crop sensor | LA-EA3 or LA-EA4 adapter* | At defaults, image cropped to the APS frame size; with this option turned off, the lens generally doesn't cover the full frame (clipped corners) |

| no modifier | full frame sensor | Full frame is covered |

* The discontinued LA-EA1 and LA-EA2 adapters can also be used, with some limitations

Sony has caused a bit of a problem for themselves with their inconsistency. In the E-mount, lenses for full frame have a modifier to identify them (FE) while in the A-mount lenses for the cropped frame have the modifier (DT). The good news is that you can put virtually all the Sony lenses on the A7 and A7r, the bad news is that almost none of the crop sensor versions of lenses come close to covering the full frame, as happens with the Nikon DX lenses and their larger-than-needed imaging circles, for instance.

One final thing. Sony’s new naming scheme means that these cameras have a longer and different name as well as the abbreviated one on the front of the camera. Thus, the A7 is also known as the ICLE-7, and the A7r is also know as the ICLE-7r. Note that these names can get confusing, too. The ICL part means “interchangeable lens camera,” the “E” means E-mount (but doesn’t define whether that’s the cropped E-mount or FE), and the number the camera number. So we get a lot of mishmash like ICLA-77, ICLE-6000, and so on. I’ll stick to the nicknames (A7 and A7r) in this review, thank you.

Neither camera has a built-in flash. The tripod socket is centered with the lens. The cameras are made in Thailand.

How Do They Handle?

Right up front let’s get this out of the way: the A7 models are a little slow to start up (apparently going to be addressed in an upcoming firmware update). Moreover, I noticed that they are a bit variable on how fast they start up, and I’m not completely sure what’s driving that. Judging from the way information appears on the screen as they power up, I suspect that they are sensitive to card differences: larger, slower cards may be taking the camera longer to deal with on power up than faster, smaller cards. That seems true in the testing I did, but I can’t guarantee that’s the only factor. So these cameras currently aren’t quite like a DSLR in the power up to shoot timing. Likewise, when you allow the camera to power down from active status, you’ll get nearly a one second delay from the time you press the shutter release to the point where a new picture will be taken.

I mention this up front because a lot of folk are seeing the A7 twins as DSLR replacements. I suppose I should write a separate article on this subject, but let me just try to correct an impression many seem to have: while mirrorless cameras come far closer to DSLR levels in many aspects today than they did a year or two ago, they’re not fully there yet. Every mirrorless user I know of that came from a DSLR can (and does) tell me about things that they are giving up. In particular, this delay in the A7/A7r on power up is very un-DSLR like. And the typical user response will be to not let the camera power down. That will chew through batteries, which also isn’t very DSLR like.

With that out of the way, let me get to the things I usually discuss in this section of a review.

Sony seems to be settling into a user interface. The A7/A7r clearly derive a lot from where Sony went with the RX1. There’s a bit of a merge going on, with elements of the NEX-7 (dials) and Sony DSLRs (menus), and recent camera designs (exposure compensation dial) all coming together into something that’s quite reasonable and usable.

For serious users, there’s plenty to like. The front and back Command dials are something that Nikon standardized on back in the 90’s, and which are arguably a reasonable way of putting lots of control into the fingers of the right hand. Where Sony differs from Nikon is that if you need to do something that requires button and dial, both the button and the dial are both “right handed.” That tends to make me move my eye from the viewfinder to accomplish, and you can’t one-hand the camera to perform most of these actions. I find Sony’s approach okay, just not optimal.

Ditto for the way menus work. In the Nikon world (and many other cameras), the Direction pad can be used to enter and exit sub-menus. On the Sony designs you have to press the center button on the Direction pad to enter, and the MENU button to exit sub-menus. If you work with many cameras, as I do, this slows you down a bit. On the other hand, using the Direction pad keys to move through the menus is direct, whereas sometimes with the Nikon style you have to exit back to the tabs and move to another menu. Again, I find Sony’s approach okay. Whether it’s optimal or not probably depends upon what other cameras you might be using.

On the other hand, we’ve got 19 menu pages to get through (100+ main options). A number of those will appear grayed out when you’re not set in a shooting mode that enables them, while others, like Peaking Level and Peaking Color, really seem like they should be combined. Put another way, Sony’s menus are logical and complete, but they could use some better editing and logical groupings. I also don’t like having to move through the networking and PlayMemories Apps menus to get to the SETUP menu (which is where the FORMAT command is, on page 5 of the SETUP menu; lots of extra scrolling for a commonly used function).

We get a whole menu devoted to PlayMemories Apps, which you may or may not find useful. As I write this, the only ones that work on the A7 twins are Time-lapse (US$9.99), Multiple Exposure (US$4.99), Lens Compensation (US$9.99), plus the free Smart Remote Control, Flickr Add-on, and Picture Effect+. Hmm. Doesn’t it seem like Sony is charging for features that are in other cameras? I sure wish Sony would really open up a real developer program, as almost nothing in their Apps list is anything that isn’t in other cameras already. It’s as if the camera companies are all studying the same play book, but we photographers really need and want some new plays. I applaud the inclusion of apps capabilities, but here we are a couple years into that experiment and I’d have to say we have nothing particularly useful to show for it.

There’s plenty of camera customization allowed via the menus. We’ve got an Fn button and three C buttons we can program. Actually, it’s far more extensive than that. We can program what the DISP button does for both the viewfinder and the LCD, we can program the control wheel around the Direction pad, the AEL button, the AF/MF button, the center button, and even the left, right, and down functions of the Control pad. Indeed, I strongly suggest that you look at all of these things and consider turning some of the defaults off. For example, the default is to have ISO on the control wheel, but that also means you can accidentally touch the control wheel and set a new ISO if you’re not careful. I prefer ISO assigned to button C1 with a dial, so I can control it and not accidentally set it.

But that’s all good news: you can actually set the camera up in ways that are functional and useful to you, and turn off (or reassign) some off the annoyances. Kudos to Sony for that. Moreover, their naming conventions and their menus to let you do all that customization are much clearer and better done than, say, Olympus’. You might have to study all the options a bit before deciding what you want where, but you won’t get a headache trying to do so, as I sometimes do with the Olympus m4/3 bodies.

But let’s get back to the DSLR-replacement notion for a moment. Do the A7/A7r shoot and handle like small DSLRs? For the most part, yes. I really can’t fault Sony’s design there: the functions are all there. I do think some of the decisions are a little sub-optimal for DSLR-type shooting (sometimes fast and intense and requiring quick reconfigurations), but not much. After my first full day of shooting with the A7 with customizations tailored to what I wanted, I had settled in to using it pretty much like I’d use a DSLR.

Still, you’ll have to make some slight adjustments. As fast as the EVF is, if you try to time things visually through the EVF, you’ll likely miss peak moment. You have to learn to anticipate a little more than you do with an OVF-based DSLR. Note that just like a DSLR, there’s blackout time in the EVF where no view is visible. That blackout is visibly longer on the A7r than on the A7, and coupled with the slower frame rate of the A7r in continuous shooting means it’s less likely you’ll like it as an “action” camera. Neither is really a great action camera, anyway, as even the A7 only achieves 2.5 fps with focus and exposure control, but if you do any motion work, the A7 is the better choice.

One frustrating aspect in shooting lots of images quickly is that when the cameras are writing to card—and remember if you pick the A7r and you’re shooting RAW+JPEG that’s a lot of information being written—you can’t review an image (Playback button) or access the menus. That’s decidedly un-DSLR like.

I tried a number of different types of photography in the months I’ve been testing these cameras. Everything from shooting basketball games to travel photography to landscapes to…well, I tried pretty much everything my limited lens set allowed. For the less action-oriented things these cameras can suffice just fine and handle like a small DSLR. Start shooting intensely, though, and that DSLR-type feeling starts to go away.

How Do They Perform?

Battery Life: I exceeded the CIPA numbers on both cameras pretty consistently, which is a good thing. I’ve got far more experience with the A7 than the A7r on this, as the A7 was purchased on day one and the A7r was a short-term loaner from B&H (disclosure: B&H is the exclusive advertiser on sansmirror.com). But I’m comfortable in saying that I can get 350-400 images in my normal shooting style with the A7. I think some of that is that with the camera customized the way I want it, I’m not dipping into the menus and using the rear LCD all that much. As usual, your mileage may vary.

Card Write Speed: Definitely invest in state-of-the-art cards. I found that write speed was definitely slower with older cards. I’d say you want 95Mbps cards or better with these cameras. Part of that has to do with the fact that you’re dealing with largish files, part with the fact that the camera doesn’t allow you to access playback or menus while it is still writing to a card. Some older Lexar 100x cards showed instantly noticeable lower performance. I didn’t even have to get out my stop watch to see the difference.

Focus: It’s probably premature to fully describe the cameras’ focusing abilities, as we only have a few lenses between 24-70mm designed for the camera available to test. I can say this: both cameras have some slight drawbacks when it comes to focus.

The A7 has phase detect on sensor, and in many situations this will tend to make it focus faster than the A7r (but not all, surprisingly). I have a number of issues with focus performance, though. First, the “spot” focus is performed on is too big (even if you select the smallest size). Coupled with some other options you’d tend to want on (like Pre-AF), even small movements of the camera can result in the camera deciding to focus not quite where you want it. In basketball shooting, for instance, I had to turn Pre-AF off, use the smallest sensing area, and still be careful to lock focus sometimes. The phase detect system was not keeping up with fast break type action and had a strong tendency to lock onto backgrounds.

On subjects not moving—or at least not moving fast—I found the A7 to be perfectly acceptable in speed, and the A7r to be a bit more variable, sometimes a bit faster sometimes a bit slower, but still acceptable. While not as fast as the latest m4/3 cameras or the Fujifilm X-T1, the A7 twins are still respectable, and we would have craved this level of focus performance two years ago from mirrorless.

Image Quality: Okay, we are now in one area where I know I’m going to get a lot of blowback: image quality. The number one thing I heard the fanboys all rejoicing about when the A7r was announced was this: “Yes! D800E quality in a smaller, lighter, less expensive body.” No, the A7r produces less than D800E quality in a less expensive body. If you want a free lunch, I suggest you try the local rescue mission.

The difference isn’t actually easy to describe because it involves what’s going on behind the covers. But let me lay out the basics: the D800E will shoot 14-bit raw files with no underlying artifacts and fully recoverable data. The A7r will shoot 11-bit raw files with potential posterization issues in the data. The same is true of the A7 versus a D610, too.

Let’s start with the 11-bit thing. Sony always uses compression in storing raw files. The way they do that is quite clever. They slice each pixel row into 32 pixel blocks. In a Bayer sensor, that means two colors, each with 16 data points). For each 16 pixels of a color, Sony looks at the minimum and maximum pixel values for each and stores that. For the other 14 pixels they store a 7-bit value that is offset from the minimum value. In essence, they get 32 pixel values stored in 32 bytes, when normally 11-bit storage for that data should take 44 bytes.

This is not lossless compression. It is highly lossy. Nor is it visually lossless. That’s because when you have an extreme set of values in the 32-pixel block (e.g. sun peaking out from behind tree edge), you get posterization of data. Don’t believe me? See this article, which describes it better than I can in the limited space of a review. Indeed, every A7/A7r owner should probably have a copy of RawDigger so that they can understand exactly where the issues in their raw files lay. Even Nikon’s optional visually lossless compression scheme does a better job at this, as it hides its posterization only in very bright values that our eyes just don’t resolve.

A number of readers of the initial review seem to take the approach “I don’t see the difference” for A7r versus D800E files. I suspect that a lot of folk won’t see differences (though they very well may see the high-contrast edge artifacts if they look close). Most of the difference that is triggered by Sony’s compression scheme relates to what most of us call micro contrast. That’s the thing that gives those medium format camera images “punch.” It takes a number of things to produce the best micro contrast. A good lens is one. Lots of pixels is another (assuming we’re looking at the final output at the same size). Non-manipulated data with deep bit depth is another. It’s on that last point that the Sony A7r fails against the D800E, in my opinion. Put simply, the D800E is producing 14-bit data values with no extra manipulation in them, the Sony is producing best case 11-bit data values, and many of those values have been calculated and are not the original data.

This factor alone means that the A7r is not equivalent to a D800E. Those of us who want high performance cameras actually want real performance, not a simulation with rounding and scaled results. (I should point out that this compression scheme is used in most Sony cameras now, including the RX1, which is where I first noticed it.)

Coupled with other issues (see Shutter Slap, below), the A7r simply doesn’t match my D800E in optimal collection of raw data. Remember, I used to write a column called Optimal Data, and that’s my mantra when shooting: collect optimal data.

Okay, so how bad is it? For some things, bad if you you’re trying to create really large prints. 32 pixels is about 1/10 of an inch in a full-size print, so you very well may see crud in your prints if you look closely. Patterned crud, which is the worse kind. So maybe I’ll do smaller prints. Okay, then why do I need 24mp or 36mp? Can you take this type of artifact out of the post processed image? Sure. But who wants to spend time looking for all the instances of it and then figuring out how to mush the posterization out?

This actually gets us into a discussion of “what can you see?” It’s been my observation that there aren’t a lot of photographers who have been trained well enough to see small defects like these. You could be perfectly happy with an A7/A7r’s raw files, right up until someone gets close to your print and says “what’s that?” Ever since I first got involved with digital imaging sensors in the 90’s, I’ve always asked for “just the data off the sensor, please.” We don’t have that choice with the Sony cameras. They always give us a managed set of data. I understand the desire to have smaller file sizes, believe me. If the Sony compression were an option, I wouldn’t have written a thing in complaint. The problem is simple: we’re never given the option of getting the full unprocessed data off the sensor. So, to Sony I say this: add a real Uncompressed Raw option. Voila. All my complaints go away, yet those that want smaller file sizes can still have them.

Note that JPEGs don’t have this problem, so it seems clear that Sony is doing the compression after the JPEG rendering is completed from the raw data. So I suppose if you’re mostly a JPEG shooter, then you can just ignore what I just wrote. I’m a little curious as to why a JPEG shooter wants full frame 24mp or 36mp sensors, though ;~).

That out of the way, what about the other image quality bits? They would be pretty much as I expect from these great sensors. Large dynamic range (as long as it isn’t in 32 adjacent pixels ;~) and clean low-noise results, even as you push into some of the higher ISO values.

Optimal ISO is about 200, not 100 for normal exposures. Fairly predictable Sony performance above that. For long exposures, optimal ISO is 100. Just as with the D800, I’d get a little skittish about going above ISO 1600 (ISO 3200 on the 24mp A7).

So what makes everyone love these 24mp and 36mp sensors? Shots like the one above, actually. We’ve got some really bright sky pieces, lots of mid-tone (including some color you really want to punch), but we also have the back side of a dark tree trunk where shadow tones usually are completely gone if you expose for the sky. I’ve only done a small touch of shadow recovery here; there’s plenty more data that I could bring up in the shadows. The problem for a shot like this with the Sony versus the Nikon implementations will come on those bright sky/dark tree boundaries in raw files. That’s exactly the type of situation where the 7-bit differential compression can end up posterizing on you.

So on the one hand, we have a strong positive: lots of dynamic range allowing us to shoot for the highlights and recover shadow detail. On the other hand we have Sony taking some of that ability away with their compression scheme. Sigh.

Let’s go to the court:

This is my usual 1.5EV underexposed ISO 3200 shot on the A7 (with the 28-70mm lens). While I’ve had to adjust my sharpening and noise reduction a bit differently than I do with the Nikon D610, this is a very respectable result. However, upon further review, I found several areas in the shot where the compression issue came up. But here’s the kicker: using Adobe’s ACR sharpening and noise reduction tends to mask those problems. However, even with the noise reduction munging pixels, I can still see some clear difference on the more vertical edges than the horizontal ones. In that blown out highlight area on the top of the ball, for example, the edge on either side of the highlight looks a bit faux compared to other places on the ball.

With the A7r, let’s look at the JPEG instead of the raw:

You should notice immediately that the colors are blocked up a bit. The net has lost some detail in the threading, though part of this is that the camera has focused further into the scene (that large sensor area I wrote about), and the edges are much rougher than I was able to obtain with ACR on the raw file. Still, considering that we should really be at ISO 9600 here, the results are pretty good. As I noted earlier, the 24mp and 36mp sensors are well liked amongst serious shooters because they hold their own even up into the higher ISO values while still giving you lots of pixels to work with. The Sony BIONZ processor seems to be doing a better job than I remember it doing on the NEX models, too, with the only big drawback here being the loss of very fine detail.

Ironically, the JPEG engine does the opposite of the raw capture: slight posterization sometimes happens in areas where there are subtle gradations in the tonal values for JPEGs, whereas it happens in high contrast areas in raw files. Coupled with the slightly heavy handed noise reduction, there’s just a bit of “grit” to the JPEG renderings on the A7 twins that could be improved with better processing. While others have written that the A7 and A7r JPEGs are disappointing in quality, I’d express that differently. I’d just say that they’re sub-optimal to what they could be. Hopefully Sony will retune the BIONZ engine and remove the things that are driving the slight deoptimization of the JPEGs.

Lens adapters: I’m not a fan of lens adapters. This actually becomes a really complex subject very quickly, but let me outline some of the problems of using lenses via adaption: mount shortness (to insure that infinity is reached) leads to slight focus errors, some lens designs lead to side to side color variation and strong vignetting, improper alignment of front and back mounts can lead to side to side focus variation, mounts without proper light deadening lead to loss of contrast and/or flare, and much more. We’re talking about a 36mp camera here (A7r). Even with only one mount and an in-specification Nikkor lens I’ve seen some slight side-to-side variation in focus plane on some D800’s. Adding another mount in the middle isn’t going to help tolerance issues for folk trying to get medium format like results. That’s not to say it can’t be done, but I’d be highly suspicious of the less expensive adapters and I’d be doing lots of testing on any that I did pick up. Be careful when reading tests of various legacy lenses mounted on adapters with the A7 twins. Some of the variability you see amongst those tests is variability in the mounts themselves. Thus, I’m highly skeptical of publishing such results myself. Adapter 1 with Lens 1 might look fine by put Lens 1 on Adapter 2 and you see issues. I don’t really know how to present a full and fair review without using a huge number of samples, so I’m going to just say: be careful. It might work for you with the right lens and adapter. But you might have issues. Nearly impossible to predict. I will say this: I can see clear side to side variation issues with a number of lenses that would need to be corrected. Leica and Fujifilm both have corrections for various Leica lenses used via adapter on their mirrorless system; Sony does not. What that means that you may have to do some color/tone correction via post processing.

Shutter slap: There’s been some controversy over whether or not there is vibration-impacted results on the A7r that’s not found on the A7. I’d say yes, there is, from about 1/15 to 1/200. The vibration, when induced to its fullest, is enough to make the 36mp A7r results look slightly worse than the 24mp A7, everything else controlled for. It definitely appears to be something related to the first curtain of the shutter, as most of the motion that causes the blurring seems to occur within the first 1/200 of a second (it takes an oscilloscope or another timed device to be able to see where the blur is occurring). Moreover, that corresponds to a difference between the two cameras: the A7r has a mechanical first curtain, the A7 does electronic first curtain. To some degree, the A7r blurring can be controlled by more mass and more integrity of the total mass (i.e. strong couplings of camera to head to tripod legs that weigh more versus weaker ones that weigh less). Is the A7r shutter slap worse than a D800’s? Yes. Clearly, and especially if you lock up the mirror on the D800 models. That’s not to say that the D800 or D800E are perfect at 1/5 to 1/200. It, too seems to have a tiny bit of first curtain shock, but it has far less visual impact on the results. Enough other people have discovered the same thing that I won’t belabor it here. I only mention it because it’s yet another factor in the “A7r is not a D800E” point I’m trying to make with this review.

Final Words

We have a lot to cover here. Let’s see if I can organize it in a logical fashion.

First up, we have the full frame sensor part. The Sony A7 is currently the lowest priced full frame sensor camera, so there’s simply a buzz that starts with pricing. And that buzz comes from one of those Internet memes: you must have a full frame camera, because “they’re better.”

This is one of the toughest things to explain well. People simply think that they must have a full frame camera because that marketing message was received and heard, but they aren’t completely aware of what the difference really gains them (some can’t even explain it, they just heard that they should have a full frame camera ;~). The camera makers of late have been encouraging this notion in their marketing, too. As I’ve noted in many other places on my sites, the difference between an APS and full frame sensor is about one stop, all else equal. Let’s consider the 24mp A7 first. What do you really gain in an A7 over a 24mp APS camera? Mostly two things: you’ll probably decide that the A7 shoots usefully at about a stop higher ISO than a 24mp APS camera (again, all else equal). If you think the 24mp APS camera usefully maxes out at ISO 3200, the 24mp A7 would do so at ISO 6400.

That may or may not be something extremely useful to you. 24mp is already a lot of pixels, and if we’re talking about taking pictures mostly to be posted to the Web (Facebook, Twitter, your Web site, etc.), you’re going to be downsizing those images and noise is already not likely going to be a real issue for any common shooting situation with a state-of-the-art 24mp APS camera. On the other hand, if your goal is 24” or larger prints of the night scene in your town, that extra stop may become significant.

The other advantage of full frame is a stop difference in depth of field capability, concentrated at the focus isolation end of the range. Every time I write something like that, I get a ton of emails saying I’m wrong about focus, so let me explain some variables here. Assume we’re trying to take the same picture with an APS and full frame camera from the same position. On the APS camera we might be using a 16mm lens to frame our shot, while on the full frame camera we'd need a 24mm lens to frame the same shot. The “extra stop” here is about depth of field. At the same aperture (say f/4), the APS camera will have more depth of field than the full frame camera: a difference of one aperture stop to be exact.

Let’s put that into numbers: the APS camera focused at five feet will have a DOF from about 3.6 to 8 feet. The full frame camera will have a DOF from 4 to 6.8 feet. To get essentially the same DOF as the APS camera, you’d need to set the full frame camera to f/5.6 instead of f/4. This is why pro photographers tend to say that full frame gives you the ability to “isolate the subject” more than APS cameras. You could, of course, move your position, use a different aperture, or maybe even change lenses, but if you’re into extreme subject isolation, you could run out of aperture on the APS camera.

These things—very high ISO capability and focus isolation—aren’t really used in all types of photography. Indeed, they might not really be useful in any photography you do. Many non-pros would value a bit more DOF over DOF isolation simply because it means they don’t have to nail focus quite so well. So right up front you have to ask yourself a serious question that only you can answer: do you really need a full frame camera? You have to ask that because a similar APS camera to the A7 might be only half the price or less, allowing you to buy more lenses and accessories with your money.

What I’m finding when people gush about the A7 and A7r to me is that they often don’t know why they need a full frame camera, they just want one. Be careful not to fall into that trap. Let me state that I’m one of the first to appreciate technical advances and small, even pixel level advantages. That’s why I use the D800 for most of my work: it’s got the best sensor out there (now shared by the A7r). But I’m also trying to push my work above and beyond that of other pros, which is no small feat. Just as most drivers don’t need autos with V8 engines in them, most photographers probably don’t need full frame, high megapixel count sensors.

The other thing about full frame that attracts people is that lenses you might have used with film cameras in the past work the same on a full frame digital camera. The Sony A7 and A7r can be used with lens adapters with virtually any lens ever made for film cameras, and this forms the second level of attraction for some. They believe that they can just pull out their old lenses and use them on this new camera. Indeed, you can. Note carefully, however, what I wrote in the performance section: there’s some variability in adapters here, plus you’ll probably be returning yourself to the world of manual focus. Nothing wrong with that, but most people are looking more for convenience and performance from a camera these days, which means autofocus.

Which brings us to the next thing you have to consider with the Sony A7 and A7r: lenses. As I write this, I only have access to four FE lenses that are designed to work with the cameras. Two of them are stunningly good (the 35mm f/2.8 and 55mm f/1.8 Zeiss). The other two—the 28-70mm f/3.5-5.6 and the 24-70mm f/4—I find less stunning. Of those two, the 24-70mm is clearly the better lens. True, there are more lenses coming (six more this year alone). But an A7/A7r user is going to be a bit constrained for autofocus lenses for a bit, so you’re technically buying the future when you opt for one of these cameras.

Okay, with all that out of the way, what do I really think?

The A7 and the A7r are really good cameras that have some limits on performance. Let’s deal with those limits first: (1) frame rate; (2) focus speed; (3) raw conversion artifacts are possible, as are some small JPEG rendering issues; and (4) the A7r has some vibration issues you need to watch for. These cameras aren’t speed demons (especially the A7r). They’re not for getting long sequences of your children’s sports activities all nicely chopped up and focused. For more casual motion, no worries. But they’re not sport cameras.

They do appeal to serious shooters and enthusiasts, though. They have a great deal of sophistication to them, excellent controls, only slight shutter/EVF lag, are excellently made, and are quite compact and light. I think that a lot of folk considering something like the Canon 6D or Nikon D610 ought to take a long look at the A7, for instance. Other than focus performance and frame rate, you’re not giving up much, but you’re potentially gaining a more manageable size and weight, a tilting LCD, and maybe even some things like the PlayMemories Apps (if Sony gets around to creating any really useful ones). The sensor in the A7 is the same as in the Nikon D610, which I consider the best 24mp full frame sensor currently available.

I’ve actually enjoyed shooting with both the A7 and A7r. They make a great generalized travel camera: highly competent, yet small enough to carry everywhere.

While everyone seems to go gaga over the 36mp A7r, it’s actually the 24mp A7 I find more attractive. Part of that has to do with the vibration issues you have to master on the A7r, but the A7 has a slightly faster frame rate and more reliable focus for objects in motion, IMHO. Part of the problem is this: the things that I want 36mp for (e.g. landscapes), just don’t have suitable lenses in the FE mount yet, and I’d be fighting the compression in the Sony raw files as well as the vibration issue. I’m hoping that the 16-35mm f/4 Zeiss that’s on the 2014 FE Road Map will be the answer to the lens problem, but if it isn’t, I might have to wait until 2015 for a lens that really does what I need 36mp for. And then I’ll still have to figure out how to either avoid the shutter shock dead zone or put enough mass into the system to settle the camera down. Moreover, I would still have to deal with the post processing of raws to get those low level posterization artifacts out. I don’t have to do any of those things with my D800E and I have a wide choice of appropriate lenses for that, so it’s going to take a lot more for Sony to pull me into the A7r world.

But on the other hand, for casual shooting I enjoyed the A7 more than I do my D610 ;~). So I keep coming back to that. Indeed, I eventually concluded that the A7 with the 35mm f/2.8 lens is essentially as good in image quality as the RX1, and way more convenient (built-in EVF) and flexible, which is why I sold my RX1. Thus, I’m amused: Sony is competing with themselves just as much, if not more so, than they are with Canon and Nikon.

If you’re a JPEG shooter, you can consider either camera, but I don’t know why you’d need 36mp other than for bragging rights. I’d say a JPEG shooter who also shoots some raw and is willing to deal with the compression issues in the raw format should take a long, hard look at the A7. I’m going to recommend it. It’s a competent camera with enough performance in focus and frame rate to handle some motion shots when necessary, and it’s a strong value at its price.

However, you have to make a decision about whether Sony will produce the lenses you eventually want and need. I think so, though I suspect that telephoto options will be minimal. For a convenient travel camera, the A7 has enough of everything you’d want to make it a contender, though, thus my recommendation.

The A7r, however, I’m not going to recommend. If we’re going to push up the sensor specs that far, that needs to be supported by better integrity in raw files and more attention to keeping the potential quality at the highest level (e.g. avoiding shutter shock). I can see why Sony made the A7r: it was easy enough to do once they opted to do the A7. Just stick in the higher count sensor and make some adjustments dictated by that. I think they should have spent more time trying to make sure that they got everything out of that sensor that they could. It’s actually a shame that they didn’t, as it comes close to being very good, just not close enough. The bragging rights for the A7r revolve solely on the number 36. They do not revolve around “highest possible quality currently available.”

As an aside, I have to say this: when Nikon hits a home run, it’s clearly out of the park. The D800E, after two years on the market, still clearly produces the highest quality images I’ve seen out of camera other than Medium Format ones, and it does so clearly. It’s the best all-around camera I know of at the moment, which is why you see me using it so much. When the A7r announcement left the bat, it looked like it could fly out of the park, too. But Sony didn’t get the bat fully on the necessary component—image quality—and the ball fell clearly inside the park. I think the fans need to sit down and wait for the next swing.

A7 Recommended (2013, 2014) no longer recommended, though. The Mark III and Mark IV models are what you should be considering instead.

Support this site by purchasing from this advertiser: